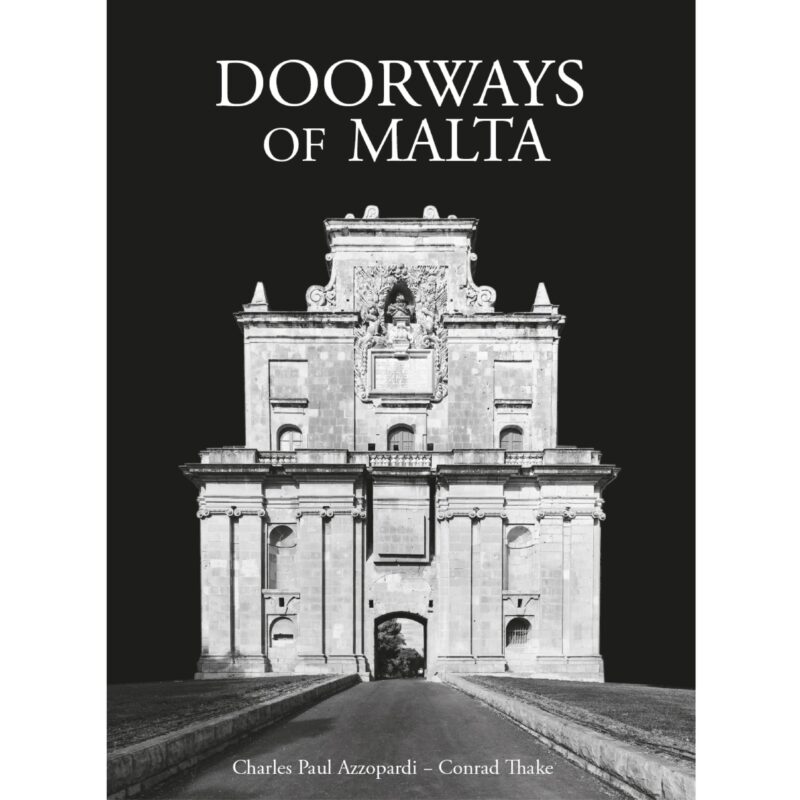

Art Nouveau to Modernism, Architecture in Malta, 1910-1950, Conrad Thake

€120.00

‘Conrad Thake has imposed on himself a forty-year time frame for his impressive research into architectural activity in Malta and its more notable exponents. The period 1910–50, is not an inordinately long stretch of time, but is still a most momentous one. Forty years that embrace, among others, no less than two world wars, the Communist revolution, the discovery of antibiotics, the rise and fall of Fascism and Nazism, the assertion of the airplane, the acceptance of abstract art, the diffusion of sound cinema and television.’

Giovanni Bonello

‘Architect Thake, with his habitual academic analyses, hones in on a period so far sparsely covered or researched: that of the architecture of the initial decades of the last century. During the first five decades of that century local architects were prone to borrowing motives from past historical styles, while also adapting imported influences from then current foreign architectural trends. As such, the local panorama of buildings of this era presents a varied and hybrid amalgam manifesting examples of Art Nouveau, menageries of resuscitated historical styles, and the initial birth-pangs of local Modernism.’

Richard England

Out of stock

Notify me when item is back in stock.

- Format:Hardback

- Pages:256

- Year:2021

- ISBN:9789918 230358

- Dimensions:28.2 × 24 cm

- Social Share:

Description

Architecture in Malta during the first half of the twentieth century has to date been a neglected area of academic research. Although there have been succinct contributions profiling some of the more prominent architects, Maltese architecture of this period has never been analyzed within the prevailing political and socio-economic context. This publication seeks to address this lacuna in local architectural history. The period under study is a tumultuous one, encompassing the First World War (1914–18), the Sette Giugno (1919), the Self-Government Constitution (1921), the suspension of that same Constitution (1930), the Language Question (mid-1930s), the Second World War (1939–45), and the Post-War Reconstruction (1943–50). It was a period of major challenges with Malta under British colonial rule, characterized by an unstable economy, distinct social classes, and political aspirations for greater

autonomy and self-governance.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 28.2 × 24 cm |

|---|

1 review for Art Nouveau to Modernism, Architecture in Malta, 1910-1950, Conrad Thake

You may also like…

-

Art

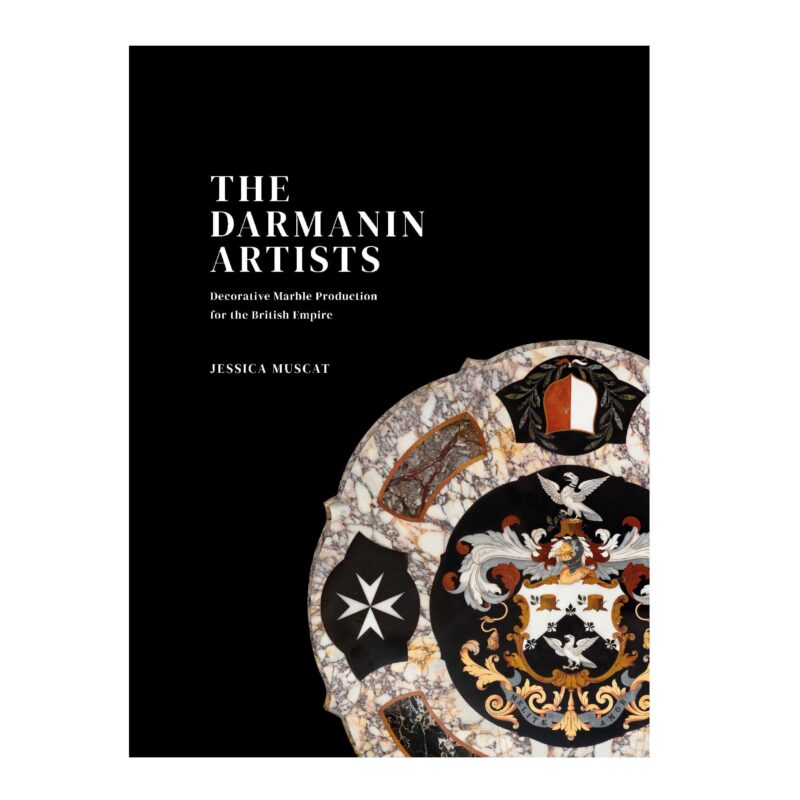

ArtThe Darmanin Artists, Decorative Marble Production for the British Empire, by Jessica Muscat.

€85.00 Add to cartQuick View -

Architecture

ArchitectureSanctuaries of the Soul, Richard England

€65.00 Add to cartQuick View -

Architecture

ArchitectureCountry Villas in XVIII Century Malta, Carmel Spiteri

€150.00 Add to cartQuick View

Edward Said –

Book review by Edward Said, published in The Sunday Times of Malta

Following much anticipation, Conrad Thake’s latest work published last month, came as a most welcome tonic to us architecture enthusiasts and nostalgiques. He had been teasing followers on social media with periodic posts portraying significant architects practising during the start of the last century. Having these personalities collected in one tome would be a first, and no-one I believe could have put this together better than Thake who in recent years has directed his research interests to particular buildings and their creators; icons which grace/d Malta’s rich architectural landscape.

As implied by its title, this book deals with a specific period of forty years which although merely half-a-lifespan amidst the vastness of our small nation’s history, was a time so dynamic, to which architecture had to adapt, and fast. A thought-provoking foreword is delivered by Judge Giovanni Bonello who sets a fitting socio-political context whilst Professor Richard England introduces the book sharing his own preferences and anecdotes, having known a number of the featured protagonists personally.

Before embarking on this architectural journey, the author provides the reader with a comprehensive overview of the eventful turn-of-the-century decades which had been characterized by an ever-strengthening economic footing. Milestones in major infrastructural and urban schemes are highlighted, these stoking two generations of architects to churn out buildings which by local standards were largely original in style.

Whilst in Europe, the struggle for a new architectural grammar had been ongoing since the late 1800s, it was significantly later that Malta reacted. The serene Victorian glory years dominated by Emmanuele Luigi Galizia, Giuseppe Bonavia, and Francesco Zammit together with interventions by British architects, notably the Royal Engineers was slowly waning. Classicism had hitherto reigned supreme in all designs architectural despite charming attempts at (oft-alien) historic revivalism, evidently in consonance with colonial tastes. Neo-classicism conceded to ornamental borrowings from the Palladian and Beaux-Arts schools. A general centuries-old fondness for Baroque still prevailed and persevered well into the new century. It was only in the wake of the Great War that proper experimentation in search of a ‘modern’ style gained some form of momentum.

Surely many a perit, now regulated by the newly-established Camera degli Architetti (1920), followed with keen interest the global leaps and bounds being made towards an innovative architecture of the time. Several more must have been somewhat frustrated by insular limitations, both in fashion as well as resources. Limestone was still the primary building material, with little else from what the Knights of St John had at their disposal. Notwithstanding, the intuitive dexterity boasted by Maltese scalpellini and capomastri was celebrated internationally, and Thake gives due credit to this venerable and most unique trade of our land. And what an embodiment of this skill was Andrea Vassallo, the first of a sequence of architects whom the author analyses in individual chapters. The professional development and output of this kapumastru-turned-perito is simply fascinating with a portfolio including many pieces which are today landmark historic monuments. What is of special interest is how Vassallo seemingly introduced Art Nouveau to Malta with Casa Said on the Sliema front, a building I heartrendingly remember being torn down back in the early 1990s. His was an Italianate interpretation of this new, modern expression, yet clients were more interested in his other traditional and historicist capabilities. Vassallo personified the transition from Victorian romanticism towards Art Nouveau in its literal definition, exemplified by exquisite mastery of Maltese stone craftsmanship, and indeed with his demise an architectural era came to an end.

Another leader comes in the figure of Giuseppe Psaila of Balluta Buildings fame, but who designed some enchanting examples of Art Nouveau and Deco residences in Sliema, most notably those on St Margaret Street. Despite Psaila’s predilection for ornamentation his employment of steel beams clad in local stone to create capacious projections and cantilevers clearly demonstrated his will to break away from traditional fully walled enclosed spaces.

Sadly, Psaila’s was a career which was prematurely stunted by a tragic accident, unlike that of his contemporary Gustavo Vincenti, who after Vassallo is arguably the most versatile Maltese architect of the early-to-mid 20th century. Here besides a professional we have a land-owner, developer and entrepreneur who was highly respected and wealthy. Together with Psaila, he spent his formative years in the studio of Annibale Lupi serving affluent clients. It is in fact intriguing to understand how the styles we associate with these three periti developed, and certainly more research on this aspect is warranted. Aside of his extensive business dealings in real estate, Vincenti’s passion for design is remarkable. Thake again dedicates an entire chapter to Vincenti, citing from previous texts by Renato Laferla and David Ellul, however a focussed publication of this key player is necessary.

Godwin Galizia followed in the footsteps of his illustrious father in the way of his diligence and love for the profession. His talents are celebrated by the author whom I know has a special interest in this dynasty and recall a captivating lecture he gave some years ago about (and inside) the Church of St Gregory the Great in Sliema, and which he now immortalises in this book. Undoubtedly there are more buildings hitherto unidentified pertaining to this younger Galizia.

It is in the final two chapters that the tempo somewhat increases with attention being turned towards the influence of politics both local and abroad on architecture. In parallel with Vincenti and Psaila, other equals were moulding their own signature styles based on their social and political leanings. We read about the fascist expressionism of Silvio Mercieca, the staunchly Mannerist monumentality of Alberto Laferla who detested anything Art Nouveau and the softer, whimsical eclecticist dreaminess of Joseph Cachia Caruana. Yet in tandem with these quasi-scenographic (and short-lived) styles other architects notably Salvatore Ellul and Joseph Colombo had looked far ahead and afield for inspiration. Their interest lay in the teachings of Adolf Loos, the Bauhaus, the already establishing International Style which they coyly tried (as architects tend to do) to promote in the design of their very homes. In the aftermath of World War Two, with reinforced concrete more readily available, the path towards Modernism was sure, particularly with the vast housing schemes as well as new institutional and industrial premises. Thake also touches on other periti who produced important landmarks and provides the reader with a useful index, thanks to which we can finally put faces to some of these gentlemen.

Art Nouveau to Modernism: Architecture in Malta 1910-1950 is a must-have for anyone who has Malta’s architectural heritage at heart. It comes to little surprise that within barely a month of publication it was fast being sold-out! The timeliness of its launch couldn’t have more poignant as it happened within days of the iconic yet beleaguered Palazzina Vincenti, to which Thake paid special tribute, was issued a conservation order in the light of a threat to its complete destruction. This state of affairs reflects the sheer lack of knowledge on architecture of the last century, particularly Maltese Modernism, which went on to mature well into the 1970s and urgently deserves an equally edifying and clear study.

The volume was published by Kite Group who have steadily built a reputation as one of the leading local publishers on art-and-cultural heritage-related themes. Most of the book is illustrated with black-and-white photographs, mainly based from the photographic collections of the Malta National Archives and the Richard Ellis Archive, and complimented by contemporary photographs taken by Charles Paul Azzopardi. There is also a selection of plates in colour also by Azzopardi highlighting the main buildings. The book also includes a comprehensive listing of synoptic biographical profiles of the architects who were active during this period with each entry accompanied by a passport-type portrait photograph of the architect.

Apart from being a valid precious addition to our libraries, Conrad Thake’s limited-edition is indeed an invaluable tool for heritage practitioners and I sincerely hope that dog-eared and note-filled copies of it soon sit on the desks of those authorities that decide which buildings are to be deemed heritage assets and given due protection.